Some developers1 recommend that you avoid using Euler angles for rotations, but we all know they are never going away. A rotation written as a yaw, pitch, and roll is far easier to interpret than a quaternion or a 3×3 matrix. If you work in graphics, robotics, aerospace, or any field that involves 3D information, you will probably encounter Euler angles.

In order to avoid hours of debugging, here is a list of common mistakes, all of which I have made in my career. This list is broken into two categories. The first three are arbitrary conventions that are either handed to you by your game engine/transforms library, or up to you when writing your own. All I request is you document your decisions; your colleagues would probably appreciate you choosing conversions they are already familiar with, which will vary by field. The last two mistakes presented are simply errors in all cases.

I assume you are already familiar with Euler angles. If not, an optional primer follows:

Aside: how do computers handle rotations?

Rotation seems simple. However, computers demand a precise definition. An intuitive solution is to decompose the rotation into three separate rotations about three orthogonal axes. You may be familiar with these as the yaw, pitch, and roll of an airplane, or as the X, Y and Z rotation in 3D modeling software like Blender. In general these formulations are called Euler angles.

Euler angles are intuitive, but difficult to work with computationally. For this, we desire a function, , such that produces the desired rotation of around the origin. Because rotation is a linear operation, this function can be described as matrix multiplication, . These matrices are called Direction Cosine Matrices (DCM). Using the Euler angles from before, and well known formula for rotations about each axis, one can construct the desired DCM:

where , and are the basic rotations about the given axis.

Euler angles and DCMs are sufficient for the needs of this article. For completeness, other formalisms include: quaternions, which are similar to DCMs but more computationally efficient, and the axis-angle representation, which is like the basic rotation matrices, but the axis of rotation may be any line passing though the origin.

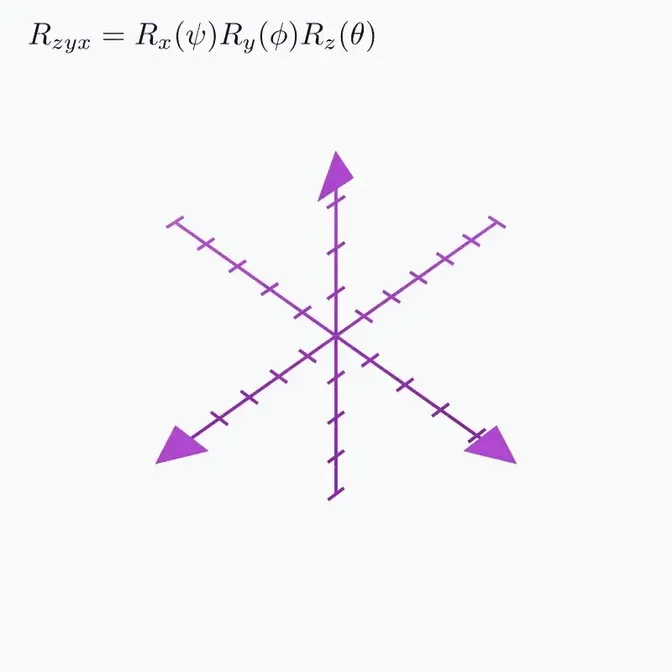

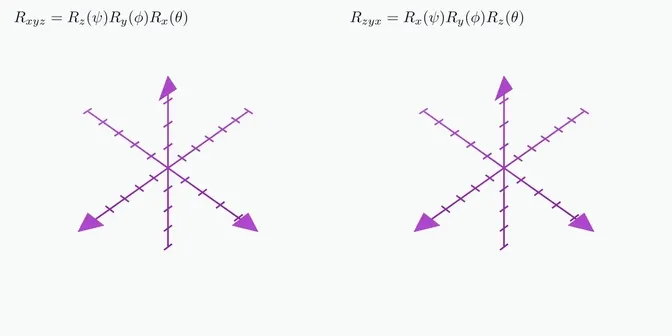

Mistake #1: Getting Axis Order Wrong

Euler angles describe a rotation by de-composing it into into three discrete rotations about two or three orthogonal axes2. The order in which these rotations occur is called the axis sequence, and is of critical importance. Because matrix multiplication is not commmunitive, the following DCMs constructed from Euler angles are not the same:

To reduce the impact of this issue, I suggest documenting which axis sequence you use, and, if possible, use only one though out a project. Also, keep in mind that the matrix expansion is written in reverse order from the sequence.

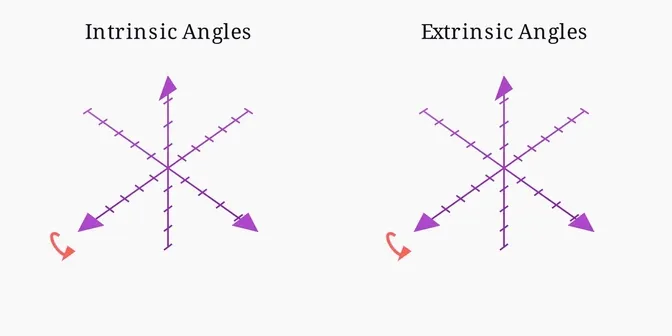

Mistake #2: Assuming Intrinsic or Extrinsic Rotations

Another common mistake is mixing up whether the rotation occur about the newly

rotated axes, known as an intrinsic rotation, or if they occur about the

original fixed axes, known as an extrinsic rotation. Getting this wrong is

equivalent to reversing the axis sequence, so these mistakes often cancel out.

That is, an intrinsic rotation xyz is identical to an extrinsic rotation

ZYX.

Once again, this is a choice you get to make, and you should document that choice.

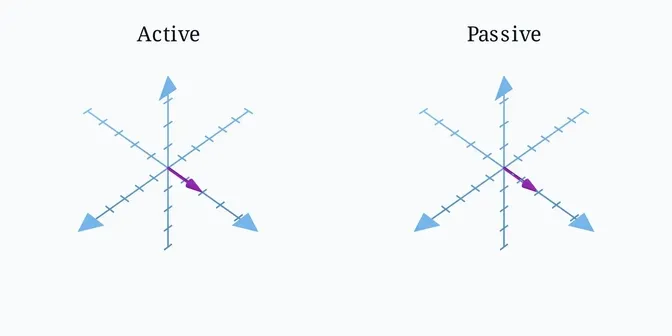

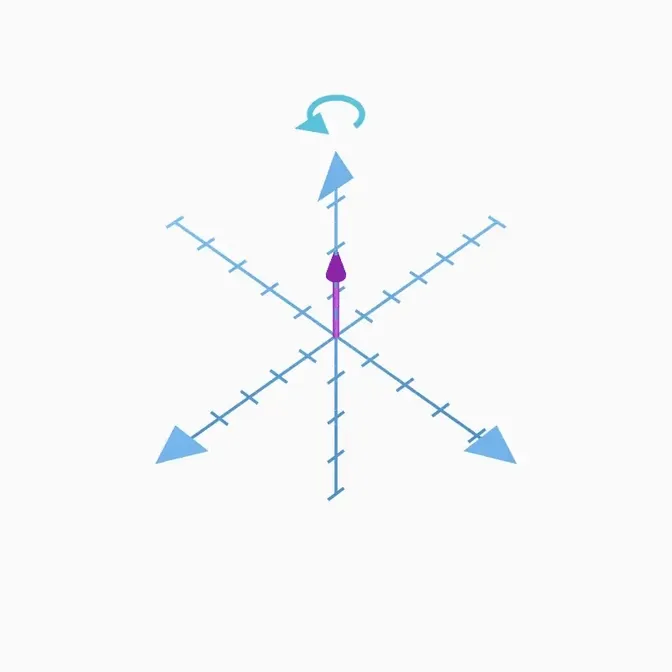

Mistake #3: Confusing Active and Passive Rotations

This is another arbitrary convention, and it applies to all rotation formalisms, not just Euler angles. The question is: does a rotation indicate an object rotating in a fixed reference frame, indicating an active rotation, or is the reference frame rotating about an object fixed in the frame, indicating a passive rotation? This often comes down to if the natural frame of reference is fixed to a moving body, such as the local level frame of an aircraft, or if there is a sensible global frame, such as the world frame of a video game. Either way, the conversion between active and passive is simply the inverse rotation.

Again, one should document their choice and use the convention best suited to your application.

Mistake #4: Assuming The Derivatives of the Euler Angles Equal the Body Rate

In part because the radius of a circle around a sphere decreases as it gets closer to the poles, the derivatives of the Euler angles are not equal to the angular velocity of an object relative to its local frame (the body frame).

Suppose is the angular rate of an object about its center in

degrees. In the zyx active formulation, the Euler angles, , will vary according to

For reasons outlines below, you will probably never need to take the derivative of euler angles, but if you have a reason to, make sure you use the right formula, instead of assuming it to be the angular velocity in the body frame.

Mistake #5: Ignoring Numerical Precision and Gimbal Lock

In the above derivatives, as approaches , approaches infinity, causing the to explode. Intuitively, a vector pointed directly up does not meaningfully change as it yaws. This phenomena is known as gimbal lock and can result in, incorrect computations due to the limited precision of computers.

The solution to this is to only use Euler angles for logging and serialization. Internally, math should be handled by a rotation matrix or a quaternion, which do not suffer from this singularity. Gimbal lock is often given as one of the major reasons to completely avoid Euler angles.

Conclusion

The complexities of using Euler angles cause some to recommend avoiding them entirely. However, there is not a more intuitive way to numerically represent a rotation, making Euler angles invaluable for debugging and exchange data between systems. Proper attention to detail, and documentation of conventions, will prevent many errors and save you time debugging.

The Figures in this Article are Licensed Under CC-BY 4.0

While I wish to retain copyright of the text of this blog post, I make all figures available under the terms of the CC-BY 4.0 License. They are free for any use, assuming attribution is given. If you do use them for something, I would love to know.

The figures are made with the wonderful Manim library made by math youtuber Three Blue One Brown.

Footnotes

-

Wikipedia3 claims that “Euler angle” only properly refers to three rotation about two axes (i.e. XYX) and that three axes rotations (i.e. XYZ) are properly called Tait-Bryan angles. However, I have ubiquitously seen the term used to refer to rotations about three distinct axes. It is true that Euler’s original formulation in Formulae Generales por Translatione Quacunque Corporum Rigidorum was a two axis rotation sequence. However, Euler himself did not refer to these angles as Euler angles. On Google N-Grams, the term seems to started becoming popular in the mid 1950s to early 1960s, by which time it seems to have mostly been used in reference to three axis rotations. 4 5 A review of A Treatise on Gyrostatics and Rotational Motion6, appearing in The Mathematical Gazette7 in 1920, does appear to call the last angle in a two axis rotation “Euler’s angle.” This source is of perticular interest, because it also mentions the work of Tait and Bryan, but only to comment on their typographical choices for the representation of fluxions. One source8 that describes three-axis rotations as Tait-Bryan angles uses Euler angle to refer to the axis-angle representation. Another source from 19409 also calls the axis-angle representation an Euler angle. Modern textbooks and libraries use Euler angle to refer to both sequences, and I will adopt that terminology. ↩

-

“Euler Angles.” Wikipedia, October 1, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler_angles. ↩

-

Buglia, James J. Analytical Method of Approximating the Motion of a Spinning Vehicle with Variable Mass and Inertia Properties Acted Upon by Several Disturbing Parameters. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1961. ↩

-

Meyer, George, Lee, Homer Q., Wehrend, William R. A Method for Expanding a Direction Cosine Matrix Into an Euler Sequence of Rotations. United States: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1967. ↩

-

Gray. A Treatise on Gyrostatics and Rotational Motion. London: Macmillan and co., limited, 1918. ↩

-

The Mathematical Gazette. United Kingdom: Bell and Hyman, 1920. ↩

-

General Rotorcraft Aeromechanical Stability Program (GRASP): Theory Manual. United States: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ames Research Center, 1990. ↩

-

Technical Memorandum - National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. United States: National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, 1940. ↩